Renaissance Perspectives

Under Your Nose: Renaissance Archival Material in the Transatlantic World

by Rowena Galavitz

Bloomington, December 2016

For the second installation of Renaissance Perspectives, continuing with the theme of “under your nose,” I’d like to tell the story of how I found my thesis topic, since it illustrates that chance and intuition are sometimes factors when it comes to doing research. Because I’m specifically interested in giving voice to the voiceless, in writing about those female creators in the early modern period who have been neglected by the modern academy, I spent part of my first summer in graduate school searching for a subject about which to write. I wanted to do research about a female mystic who wrote in Spanish in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. As such, I read articles, scanned books, and mined databases like Bieses—and came up with nothing but a few leads.1 Mind you, I had already found a four-volume historiography book on late medieval and early modern Spanish women writers, which lists approximately 500 authors.2 Of these, most of us could only recognize a few names. Teresa of Ávila, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, and, more recently, María de Zayas are perhaps the best known women who have made it into the Golden Age canon. Of course not all of those approximately 500 authors are still worthy of study today, but these numbers tell us that there’s a lot more work to be done on early modern women. Fortunately, book series such as The Other Voice in Early Modern Europe provide a venue for scholars working on lesser known creators.3 At any rate, the four volumes rendered nothing of note for me, and I left for a visit to Oaxaca, Mexico, my former residence, empty-handed in terms of a thesis topic.

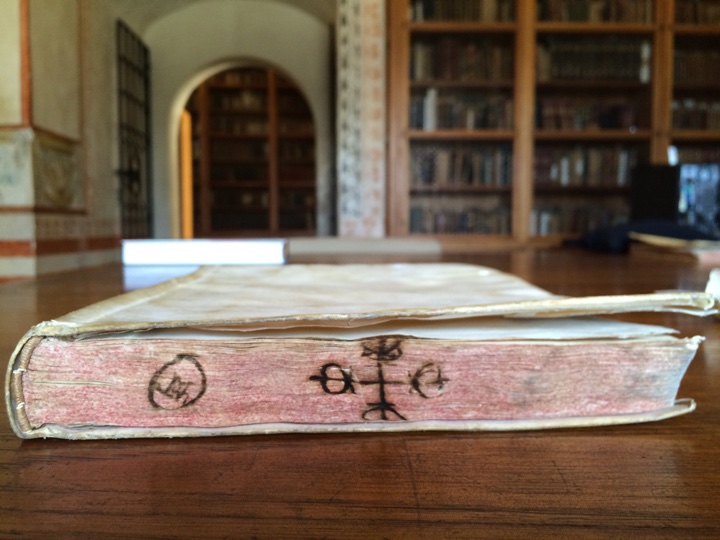

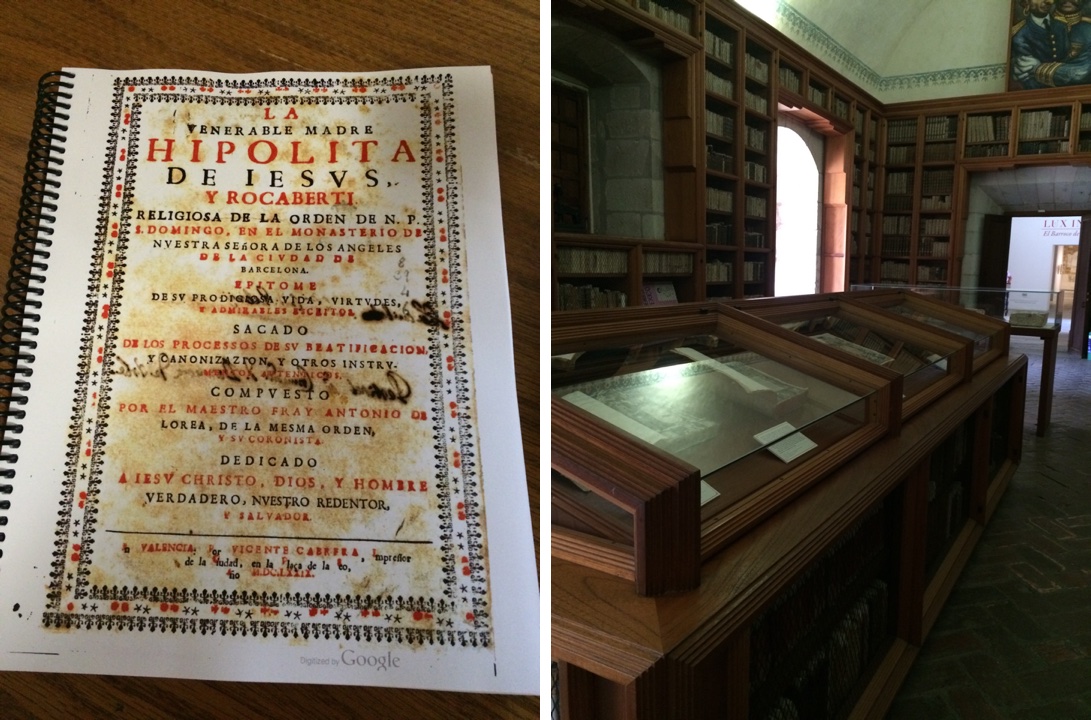

While there, on a hunch I visited the Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa, a library housed within the marvelous Centro Cultural Santo Domingo. The center itself is an enormous two-story ex-convent turned museum, which was impressively renovated in the 90s. Asking, almost embarrassingly, if they happened to have any books by women mystics, the librarian enthusiastically told me the archive had about twenty books by a single mystic, Hipólita de Jesus, a seventeenth-century Dominican nun who wrote in Spanish, Catalan, and Latin. She handed me an early print volume bound in vellum with “fire brands” on the spine—marks used by convents and monasteries in colonial times to identify their books (Figs. 1 and 2).4 After perusing the text for a while, I knew I had found my author, but it was my last day in Oaxaca! I quickly took some notes, and when I got back to Indiana, I realized some of those volumes were available in digital form. From there, I combined several physical visits to Mexico with digital humanities work by downloading and printing a couple of books from the Internet and binding them (Fig. 3). I also did my transcription and translation work directly in the PDF file using Adobe Acrobat. The funny thing was that when I actually lived in Oaxaca, it never occurred to me to do research in that library. Now, I’ve developed professional relationships with the staff, and they’ve asked me to curate an exhibit of Hipólita’s books in the summer.

Fig. 1. Hipólita de Jesús, y Rocabertí. Libro Primero de Su Admirable Vida, y Dotrina, que Escrivio de Su Mano, Valencia: Francisco Mestre, 1679. Print. Courtesy of Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa, Oaxaca, Mexico.

Fig. 2. Hipólita de Jesús, y Rocabertí. Libro Primero de Su Admirable Vida, y Dotrina, que Escrivio de Su Mano, Valencia: Francisco Mestre, 1679. Print. Courtesy of Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa, Oaxaca, Mexico.

This experience demonstrates that we should never underestimate the resources available to us where we live or study and that archives in former European colonies can be fabulous places for material because there was a wide interchange of books in the early modern Atlantic world, especially when it comes to the religious orders. Additionally, digital forms of early modern books can complement archival work as long as we bear in mind that even in the age of print each copy should be seen as unique.

Fig. 3 (left). Hipólita de Jesús, y Rocabertí. Libro Primero de Su Admirable Vida, y Dotrina, que Escrivio de Su Mano, Valencia: Francisco Mestre, 1679. Google Books. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

Fig. 4 (right). Biblioteca Francisco de Burgoa, Oaxaca, Mexico.

Oaxaca has some incredible archives. The library where I did my research holds over 30,000 titles, most of which belonged to the local Dominican order, on a wide variety of subjects and in European and indigenous languages (Fig. 4). Some of these books even escaped the hands of the Spanish Inquisition. One special feature of the collection is the late seventeenth-century Polyglot Bible published in Ambers and edited by Benito Arias Montano. For those who may be doing research on Mexican indigenous culture, the Biblioteca de Investigación Juan de Córdova, has a large collection of books, maps, photographs, and textiles available for consultation in person and online. Finally, just today the Historical Archive of the State of Oaxaca, with more colonial holdings, was inaugurated. Surely there are some treasures there. These are just a few of the many archives relevant to Renaissance research to be found in this city. So, remember, when it comes to investigation, follow your nose… and your gut.

- 1. Bieses. “Bibliografá de Escritoras en Español” (Bibliography of Women Writers in Spanish. Bieses.net. Web. 28 Oct. 2016. ↩

- 2. Manuel Serrano y Sanz. Apuntes para una biblioteca de escritoras españolas desde el año 1401 al 1833. Madrid: Establecimiento Tipolitográfico, 1903-1905. (4 vols.) Hathitrust.org. Web. 28 Oct. 2016. ↩

- 3. https://www.othervoiceineme.com/othervoice-toronto.html. Web. 28 Oct. 2016. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/series/OVIEME.html ↩

- 4. For more on fire brands of the various religious orders in colonial Mexico, see: Catalogo Colectivo de Marcas de Fuego (Collective Catalogue of Fire Brands). BUAP. Web. 28 Oct. 2016. ↩

Having recently completed an M.A. in European Studies at Indiana University, Rowena Galavitz is the 2016-17 Renaissance Studies Graduate Fellow, as she begins the doctoral program at IU in Religious Studies and Comparative Literature. Her academic interests include convent writing, mystical literature, sainthood, gender, and sexuality in late medieval Europe, early modern Spain, and colonial Latin America.

Having recently completed an M.A. in European Studies at Indiana University, Rowena Galavitz is the 2016-17 Renaissance Studies Graduate Fellow, as she begins the doctoral program at IU in Religious Studies and Comparative Literature. Her academic interests include convent writing, mystical literature, sainthood, gender, and sexuality in late medieval Europe, early modern Spain, and colonial Latin America.